Throughout the 40-year information age, we continued to educate young people as if computers didn’t exist. We teach courses that focus on memorization. We teach long division and polynomial factorization as if they were important skills. We gave small problems with known answers when the real added value was solving big problems we had never seen before (like climate change and pandemics).

We are now four years into the Innovation Age, with enormous computing power and code that can be learned – sometimes in beneficial ways (e.g., drug discovery) and sometimes in harmful ways (e.g., the social media information gully). Novelty, complexity and speed are the mantra in every field. Opportunities have never been greater and inequality has never spread so quickly.

To add value, people should learn what computers can’t do. That’s the conclusion of Jamie Merisotis’ new book, Human Work in the Age of Intelligent Machines. As CEO of the Lumina Foundation, Merisotis has a good view of the future of work. He believes that computers will become smarter and more powerful and replace many repetitive jobs and even eliminate some altogether in the next decade.

Merisotis says that the added value lies in “human traits such as compassion, empathy and morality,” as well as “interpersonal, problem-solving and general skills.”

According to Merisotis, “the worlds of work and learning are merging into a single system based on credentials with clear and transparent implications.” Therefore, schools should focus on the skills that matter most – skills unique to humans, skills that utilize intelligent machines.

The old boundaries of studying for 3r 12 (or 16) years and then working for 40 years no longer exist. “Human work,” says Merisotis, “by its very nature of earning, learning, and serving, requires the full range of our abilities and capacities.”

He advocates breaking down the traditional barriers between work and learning, early access to work-based learning, and lifelong access to learning opportunities. Just as Kansas City’s Real World Learning program will result in high school graduates with valuable experiences and credentials, Merisotis urges that learning goals reflect the skills and dispositions that matter most for citizenship and contribution.

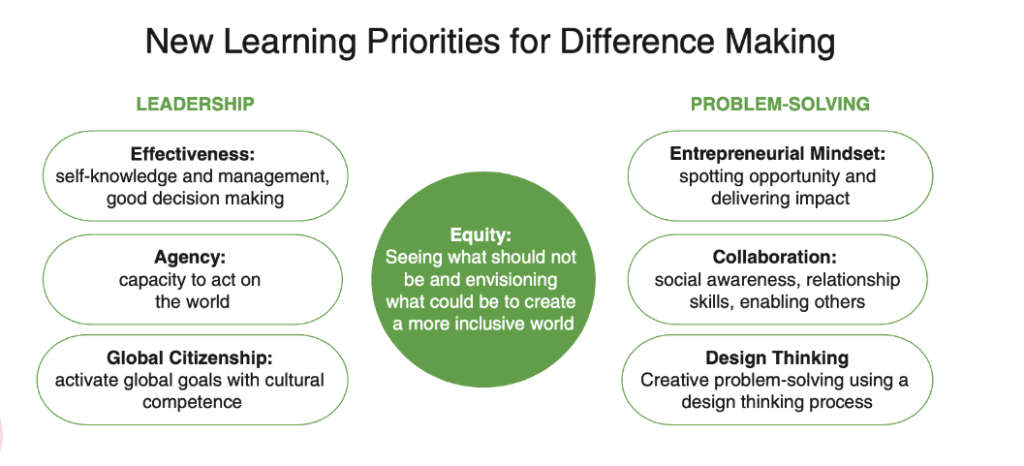

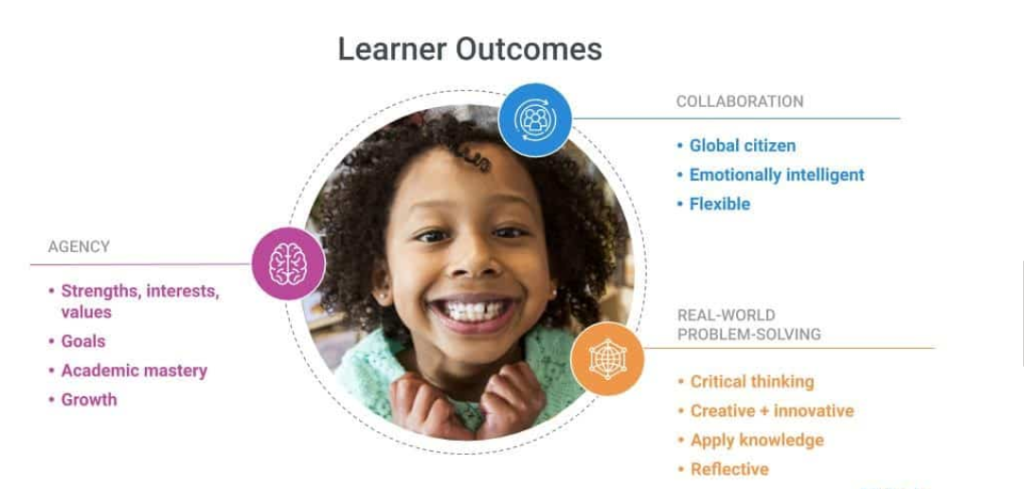

Like Merisotis, our colleagues at Altitude Learning urge learners to achieve new outcomes: agency, collaboration, and the ability to solve real-world problems (featured image). The framework combines a student-centered approach, social and emotional learning, and global citizenship, all in a very concise, easy-to-use and memorable framework.

Schools adopt new learning goals

The problem that needs to be addressed is that school success is currently defined by test scores and a list of courses attended – both of which are weak signals of interest and ability.

Inventing Opportunity (with a bit of unexpected epidemic flexibility) articulates a new and relevant shared mission and learner goals that prioritize success skills, well-being, and contribution.

Thousands of schools have adopted new learning goals that include the development of critical thinking, communication, collaboration, creativity, and other 21st century skills that young people need to thrive in this complex, rapidly changing world.

Schools in the EL Education Network share a character framework based on purpose, agency, and belonging. At the heart of developing effective learners and ethical people is learning to contribute to a better world.

The XQ Learner Goals encourage young people to become “original thinkers in an uncertain world” (meaning-makers and generative, creative problem-solvers), “generous collaborators on tough problems” (curious world citizens and self-aware team players), and “lifelong learners.”

Summit Public Schools has a broader definition of success and has created a comprehensive results framework based on Turnaround’s Learning Building Blocks (discussed in this post on curiosity).

CZI, which shares the Summit platform through a network of 400 schools, has a whole-child development framework based on six domains: academic development, cognitive development, identity development, social-emotional development, mental health, and physical health. (You’ll soon see a great new outcomes framework based on these six dimensions.)

The crisis may be a good time for your school to prioritize making a difference in your community. Our new book shows that making a difference is a great way to build agency, exercise leadership, and practice problem solving.

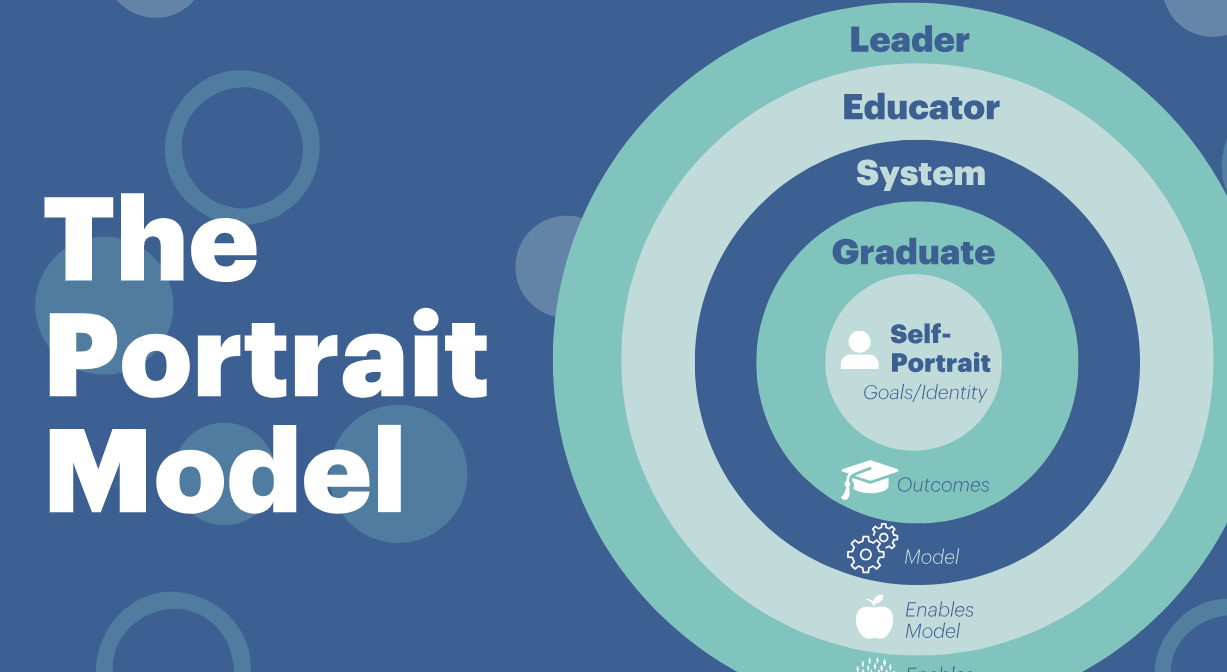

These outcomes frameworks can be used as student learning goals or graduate student portfolios, but making them a reality requires translating them into grade-spanning expectations and embedding them in culture, curriculum, and communication.

Administrators in the North Kansas City School District gathered yesterday to enrich their program with learning goals – resilience, empathy, learner mindfulness, communication, problem solving and collaboration. The district is committed to making the portrait of a graduate a reality by embedding competencies throughout the system.

Reconsidering learning goals in the midst of a crisis may seem ambitious, but it’s a good time to clarify what’s most important.

How children grow, not what they should know

As communities consider new learning goals, it’s important to consider the protective factors surrounding students-such as family support, connection to culture, daily activities, and consistency in school.

The Building Blocks in Turnaround illustrate that without a strong foundation of belonging, habits of self-regulation, resilience to manage stress, and a growth mindset, you can’t achieve higher-level outcomes.

“Dr. Christina Theokas, Vice President of Applied Science at Transform Kids, says that as a developmental process, the building blocks help teams of teachers “reimagine the goals of adolescent learning beyond academic standards, and then realize that these skills and mindsets require the same design, attention, and support as academic skills. support as academic skills.”

Theokas, who helps schools incorporate developmental supports into their systems and practices, adds that these building blocks “need to be integrated into authentic learning experiences, modeled, and provide opportunities to transfer their learning to new environments.”

To turn all the D’s and F’s into C’s (curiosity) and A’s (agency) during this pandemic, teachers need to focus on individual factors and the environment surrounding the individual learner.

In order to provide this complete child support for students, schools and communities need to provide complete teacher support (remember, there are a lot of teachers out there who are trying to teach your child as well as their own).

I know it’s crazy, but it might be time to consider a simpler set of student-centered learning goals like agency, collaboration, and real-world problem solving. They can provide a much-needed sense of prioritization and freedom to support learner learning.