Increasingly, schools are helping students to engage in their own learning through initiatives that build agency, voice, and instructional input.

Student agency requires that every student has a sense of belonging in all classes and activities. True student agency also relies on rigorous teaching and learning and on understanding each student in a “whole person” way.

So what is student agency? While there is no single definition, some common elements have emerged to describe it. Jennifer Davis Poon, a researcher at the Center for Innovation in Education, summarizes four core concepts of student agency.

- Setting favorable goals.

- Taking action to achieve those goals.

- Reflecting on and normalizing progress toward those goals.

- Creating a belief in self-efficacy.

In Poon’s framework, there is student voice and choice, as well as ownership-other terms that are repeated in today’s efforts to transform education by engaging students. The following example demonstrates the power of the framework.

When a student notices injustice, not just in bullying, but when they become an ally to their peers’ learning.

For Scott Kavanias, principal of Alvarado Middle School in Rowland Heights, California, student agency means “making sure students have a seat at the table.” He and his team look for opportunities for students to have a voice in their learning and to showcase their gifts and talents; then, teachers and staff can celebrate those holidays.

Kavanias also emphasized the importance of fostering alliances for student voice. By this he means that students have the ability to advocate for themselves and others. He said, “When a student notices injustice, it’s not just in bullying, it’s when they become an ally to their classmates’ learning.” For example, noticing that another student may need help with reading or more time to deal with a problem.

Is It Worth It?

Rethinking classroom practice and design to spend more time getting students into the teaching-learning equation seems like a daunting endeavor. Is it even possible to accomplish this at the elementary level?

There are many reasons to enhance and expand student agency. One reason is that it can dramatically increase the motivation of students to engage in learning, even those younger students who are already enthusiastic about beginning their learning journey. Motivation – especially intrinsic motivation – is a key factor in learning.

Motivation is a factor that connects to cognitive flexibility and self-regulation in early grades for critical thinking, mastery of content, and collaboration with peers. Other reasons to promote student agency and voice are to help develop self-awareness, social awareness, self-management, and more. These skills – along with cognitive and content development – will lead students out of the classroom and into the outside world.

One third grader said, “When teachers give us choices, it helps me learn because I can choose what I know best or I can choose what I want to know.”

Building the Foundations

While fostering student agency can increase student motivation, developing that motivation will depend on the strength of the relationship between the student and the teacher and the student.

A fifth-grader at Villacorta Elementary School said, “It’s important to build relationships because we’re like a second family and we always work with each other.” “When you have a good relationship with someone, it’s easy to learn with them.”

Before student agency and voice can take over, learners must feel safe and trust their teachers and the school community as a whole. In order to develop this trust, learners need to know that those around them understand their uniqueness, including their cultural backgrounds and academic needs. By building relationships, teachers can also model key social skills such as collaboration, empathy, respect, and compassion. In other words, “It’s good for another person to be famous,” says a fifth-grader with ADHD and autism.

“Having important conversations with students is key,” said Julie Mitchell, superintendent of the Rowland Unified School District (RUSD). “Just because a person has the title of educator and they’re a student doesn’t diminish their role.”

Listening to Student Voices

Here are examples of school and district efforts to cultivate and nurture student activism and voice, and the results they’ve achieved.

Conference Program. “The Students for Equitable Education Summit, a multi-district, national effort, is creating a student-led conference that empowers students to affect change in school design and operations.

Led by Mitchell and Middletown, Ohio, schools chief Marlon Styles this past April, the SEE Summit brought together high school students, teachers, and mentors for a virtual conference. Students chose conference topics, such as “Teaching Real History and Real Current Events on Social Justice Issues” and “Cultural Inclusion and Encouraging Diverse Expression,” and worked with assigned mentors to develop each session.

In the wake of the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis and the subsequent development of the Black Lives Matter movement, both chancellors agreed that efforts should be made to promote student agency and voice, build stronger relationships between students and faculty, and increase collaboration. strong relationships, and to strengthen a collaborative school culture, the days of which are long gone.

While this is a high school program, its intent can serve as a model for young students to identify topics that are important to them, to celebrate who they are and who their peers are, to collaborate with their class or school, to create activities for them and with them, and to build strong and trusting relationships with their teachers.

Make sure all voices are heard. Alvarado Middle School emphasizes four core beliefs that pave the way for student agency and voice: all students are gifted; all students have a future; all students need teachers in the classroom, with their peers, at home, and in the community; and every day is an opportunity to become the greatest version of themselves. Using these core beliefs, Alvarado’s goal of developing student can-do’s and voices is built on recognizing and respecting the voices of others-what Kavanias calls allyship.

Says Instructional Coach Jessica Delavigne, “When student voice is not based on beliefs that include all students, you run the risk that only certain groups of kids feel empowered.” “We make sure to align with our core beliefs to prevent this from happening and to ensure the sustainability and authenticity of each student’s voice.”

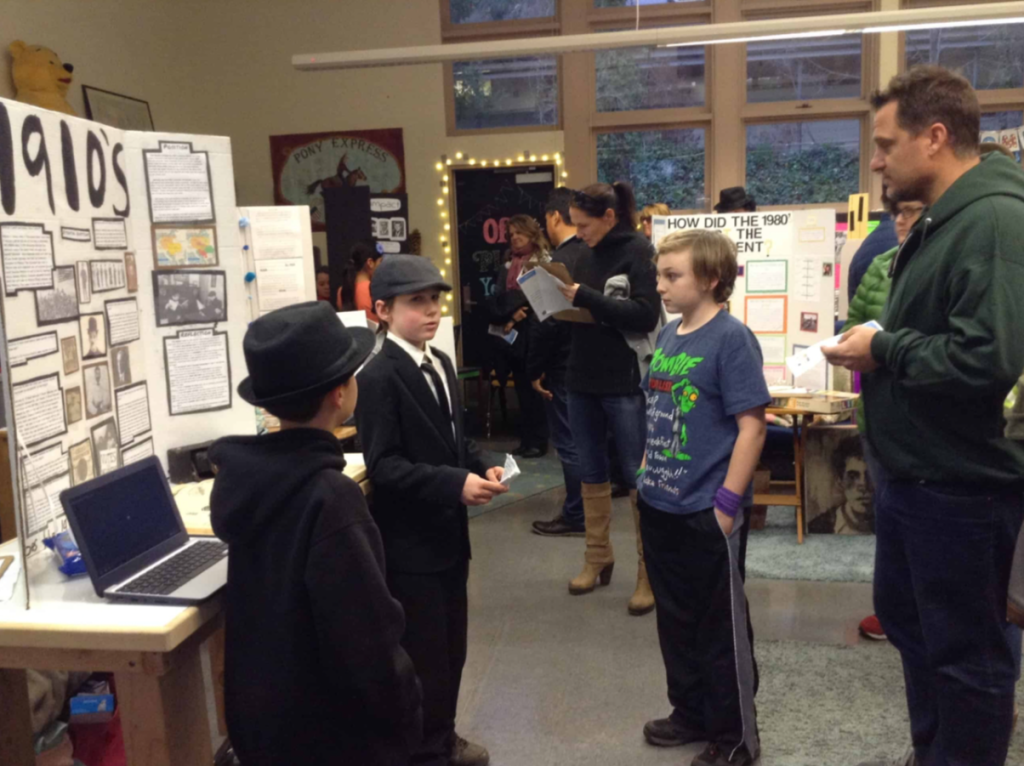

Kavanias said authentic student voice can also be realized through the school’s three r’s:Relationships, Responsive Teaching Practices, and Reflection. The school combines these with its core beliefs to form a school-wide project-based learning (PBL) approach that culminates in the Student-Led Learning Showcase, a day-long presentation tour of student self-selected projects.

Kavanias and Delavigne are proud that all students were able to participate, choose a project, and decide how to present it. In the process, they collaborated with each other, connected with their faculty mentors, learned to express themselves, and reflected on what worked and what could be improved.

More voice in math. At Villacorta Elementary School (VES), the paradigm has shifted from focusing solely on the right answer to fostering an appreciation for the thinking behind the answer. This is where student voice comes into play.

Moving to an asset-building approach validates students’ thought processes, and the end result is more agency, voice, and overall engagement in math. Principal George Herrera says he can tell which students “grow up on campus longer because they’re more willing to take risks-more willing to explore, more willing to find out what they’re doing wrong.”

One third-grader said, “I study harder because I feel like I’m in control of my learning when I get to choose the classes I’m most interested in.”

The students worked with their teachers to solve problems and then broke into groups to figure out how to solve them. Herrera said, “They understand this part, but not that part, and it’s a shift from saying, ‘I got the wrong answer,’ to thinking about the process.”

While there are still math tests, “there’s a difference between rote memorization and providing an experience that improves test scores,” he adds. The goal is to make scores “part of good learning and good skills.”

Hard-learning minds. At Ibarra Academy of Arts and Technology in Walnut, California, social-emotional learning (SEL) and spaces for adventure in the classroom and throughout the school “provide a highway for us to listen to the voices of our students,” says principal Annette Ramirez. “We want to get to know our students, not just the learners.” The school hosts “Identity Day,” a day when students and teachers share who they are to build relationships and trust.

Ramirez attributes Ybarra’s strength in fostering student voice, at least in part, to the fact that it is an International Baccalaureate (IB) school with student-led learning. Through professional learning experiences, teachers develop an understanding that student talk, rather than teacher lectures, can motivate and help students express their needs. She says, “Inquiry-based teaching is entirely student agency.”

Teachers in the early grades work with learners to create a risk-free environment. Students choose their own projects, and in the transition from kindergarten to first grade, teachers use play-based learning to provide opportunities to express voice and choice.

Arguing for agency. In partnership with Argument-Centered Education (ACE), Brooklyn Lab (LAB) Charter School in New York City moved student agency and voice to the debate stage this year. The debate theme focused on two issues: one on COVID-19 protocols and discipline; the other on vaccines Students delved into research, formed opinions, and engaged in civic debate.

It takes a conscious effort to lay the groundwork and provide learners with the trust and confidence they need to take charge of their own learning.

One goal, says Eric Tucker, co-founder and executive director of the Lab, is to “help school communities work through the available evidence and take ownership of informed and equitable public health choices in the process.” Another is to strengthen the voice of students in grades 6-12 in schools through evidence-based discussion and exploration.

The protocols for debate provide for civil discourse, while the evidence-based protocols provide rigor for students to develop critical thinking. Within this framework, students support their voices with facts and learn how to recognize and civilly discuss opposing viewpoints. “Organized debate is a way for people to respectfully and productively express different opinions,” Les Lynn, founder and CEO of Tucker and Debate-Centered Education, recently wrote in the Chicago Tribune.

Student agency and voice is not a light switch that can be flipped on suddenly. It requires a conscious effort to lay the groundwork and provide learners with the trust and confidence they need to take charge of their own learning.

Styles said, “Imagine if instead of giving students our platform to amplify their voices, educators gave students the platform they want and need to amplify their voices.” “If students got what they needed, imagine the impact they would have on the world.”